The current war

To end it

Learning about the past

To end it

Learning about the past

#Asia University research

OHARA Shunichiro Associate Professor

Faculty of Law Department of Law

2025.09.01

In our series "If it's not interesting, it's not academia!", we introduce research content and anecdotes of Asia University faculty members. The 16th installment features Associate Professor OHARA Shunichiro Faculty of Law Department of Law.

The world was changing dramatically during my junior and senior high school years

I have been interested in international politics related to war and peace since I was in junior high and high school. At the time, the world was undergoing major changes, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. I followed the dramatic changes in the international community in real time through the news, and even in my contemporary social studies classes in high school, we discussed the topic of "What will become of the Japan-US alliance in the future?"

At the time, I often watched commercial television political debate programs and often found myself resonating with the views of international political scientist Masataka Kosaka, who appeared as a commentator. Reading his book, "Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru," I was reminded once again that diplomacy is a creative endeavor aimed at creating peace. Yoshida Shigeru, a former diplomat and politician, was instrumental in resolving postwar Japan's chaos and, through diplomacy, reestablishing Japan's presence in the international community. He dedicated himself to building the nation that led to the Japan of today. Yoshida's words, "lose the war, win through diplomacy," symbolize his historical understanding of diplomacy and are related to the Congress of Vienna (1814/15), where countries discussed the European international order after the Napoleonic Wars, which later became one of my main research topics. They also echo the diplomacy of France, which secured its position as a great power despite being defeated at the Congress.

At the Congress of Vienna, Austrian Foreign Minister Metternich, with the cooperation of British Foreign Secretary Castlereagh, established a European international order (the Vienna System) based on cooperation among European countries and a stable multipolar structure. This "multipolar" structure, in which all major European powers held roughly equal power, was formed, and the interests of smaller countries were carefully woven in between. As a result, no nation or power attempted to directly overthrow this international order, and for the next 100 years or so, no major wars involving all of Europe occurred. During the Vienna System's heyday, from 1815 to 1822, a highly sophisticated collective security system was operated, centered around the Quadruple Alliance (which was joined by France in 1818 to form the Quintuple Alliance), which included all of Europe's major powers.

"What can we do to build a peaceful international order?" Having studied international law under Professor Shimada Yukio at Waseda University, I decided to seriously research multilateral cooperation and an international order based on a stable multipolar structure, so I went on to Graduate School at Kyoto University, where Professor Kosaka was enrolled, and studied under Professor Nakanishi Terumasa, an international political scientist who was one of Professor Kosaka's students.

The 19th century "Vienna System" and "systems thinking" are the starting point for lasting peace

I aspired to become an international political scientist rather than a politician or diplomat because I wanted to deepen my thinking about the international order based on cooperation and multipolarity from a broader and more comprehensive perspective from the very beginning of my career. I was fortunate to have conducted a comprehensive examination of the history of international politics over the past 500 years, from the emergence of international politics at the end of the 15th century (1494) to the present, from the Graduate School and postdoctoral days at Kyoto University, and from my arrival at Asia University to the present. In the following section, I would like to talk about the contents of the article.

In the first place, there are two premises behind the establishment of an extremely complete international order under the Vienna System. The first premise is the maturity of the soft side of the European international order in the late 17th and 18th centuries. At the same time that the Enlightenment was at its peak, the rationalist knowledge of philosophers and thinkers from German and French countries, including Pufendorff, Leibniz, Saint=Pierre, Rousseau, Wolff, and Vatttel, blossomed into "ideas related to collective security" and "ideas of international law", which were shared with politicians and diplomats in European countries. The European international order has matured on the soft side.

The second premise is that the process of maturation of the European international order has been clarified and visualized by a full-fledged research book. In 1809, just before Metternich began to lead international politics to European countries in earnest, a comprehensive research book on the maturation process of the European international order in the 15th~18th centuries was published, compiled by a German historian named Helen, which played a major role. Helen is a historian who is active as a Professor at the University of Göttingen and is regarded as the founder of the "German School of History" in international political history.

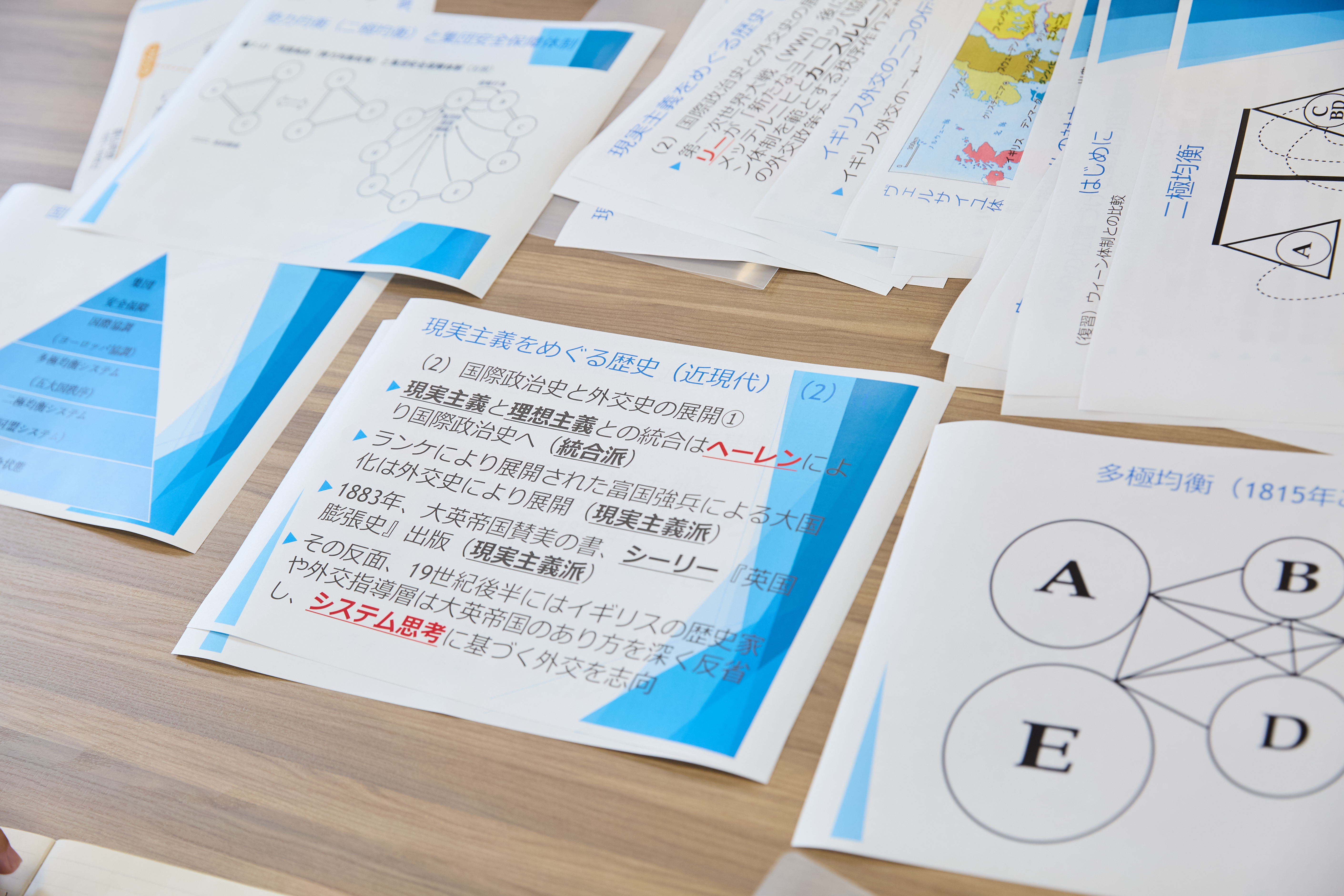

The European international order matured step by step from the 15th century to the early 19th century. First, (1) the "state of war" seen in the Italian War and the Thirty Years' War, (2) the "bipolar equilibrium" in which countries form a grand alliance against countries aiming for hegemony, such as Charles V's Habsburg Empire and Louis XIV's France, and (3) the "multipolar equilibrium" in which many great powers disperse and have power to form a harmonious balance when the grand alliance of various countries wins. We will proceed with the maturation of the hard side step by step. On top of this, the maturity of the soft side that I mentioned earlier was combined to form (4) "international cooperation (great powers)" operated by consensus among major powers, and (5) the "collective security system" in the early 19th century (1815~1822).

Against the backdrop of this maturation of the European international order as a "system," diplomatic thinking will undergo major changes. In the 18th century, in continental countries such as Germany and France, centered on Austria and Prussia, "systems thinking" became established to define diplomatic behavior based on the stability of the international order. To put it more precisely, "systems thinking" is a diplomatic thought that prioritizes the stability of the international community as a whole and pursues national interests within the scope of system stability, based on an understanding of the maturation process of the international system from the 15th century to the early 19th century. And the opposite of this was "opportunism". "Opportunism" is positioned as a diplomatic ideology that seeks every opportunity to promote national interests, and as a result, undermines the stability of the international system. In the countries of continental Europe in the 18th century, the mainstream of diplomatic thought changed from "opportunism" to "systems thinking", which strongly encouraged the maturity of the European international order. In other words, as countries emphasized diplomacy based on social considerations called "system thinking" rather than diplomacy based on selfishness called "opportunism", the international order changed (socialized) into an "international community" as a social union. Helen's achievement was research, which comprehensively summarized the maturity of the European international order as a "system" and "society." In other words, before the activities of Metternich and Karslerle, a specific methodology was established on how to create a stable and lasting peace order through the "power of learning".

By the way, in the period until the Vienna system in the first half of the 19th century, the center of "systems thinking" was on the continental side such as Germany and France, but "system thinking" was not mature in England until then. Originally, in Britain, there was no custom of thinking about diplomacy and international politics with the concept of "system", and in Britain during the Vienna System, "systems thinking" was understood only by a limited number of people who had close ties to Metternich, such as Carsleigh and Wellington. Rather, Britain's diplomatic guidance tended to focus on "opportunism" as represented by Canning and Palmerston, and to be eager to expand the British Empire. In the Seven Years' War in the mid-18th century, Frederick II of Prussia, who was betrayed by Britain's "opportunism" at the end of the war, criticized British diplomacy at the time in the sense that "Britain does not have the idea of systematically thinking about international politics", and "the dishonest white island (England)" was also synonymous with opportunistic British diplomacy. This point is described in the famous Harold Nicholson's book "Diplomacy".

However, when Helen's research was translated into English in 1834, British diplomacy gradually changed. The German word "Staatensystem", which had been used to refer to the "system of states (international system)" in Helen's English translation, was translated as "states system" for the first time in the English-speaking world, and as close academic exchanges with Germany developed, "system thinking" that thinks about international politics with the concept of "system" gradually became popular in the United Kingdom became established.

This is because in the 19th century, academic exchanges between research German and British scholars were active, and research who had mastered German full-fledged scholarship took up important positions at Oxford and Cambridge universities. Sir John Acton, who studied at the University of Munich for seven years and held the top Professor position of Professor (Regius Professor) in charge of the Course of modern history at the University of Cambridge, is a typical example. Especially after the reunification of Germany in 1871, German universities occupied the world's throne and were ranked among the world's research in all fields, and Germany was the first destination for research and social leaders in both the United States and the United Kingdom.

In this context, even in the international political research that was carried out within the framework of history, the research of the "German School of History" based on the aforementioned "history of international politics with Helen as the founder" and "diplomatic history with Ranke as the originator" will have an impact on the world. The Course of "Diplomatic History" established at Tokyo College (now Waseda University) and Tokyo Imperial University during the Meiji era is also the source of international politics and international relations theory in the current Japan, but it was established as the study of the "German School of History" spread around the world. Not only the "diplomatic history" represented by Nagao Ariga, but also the entire "political science" represented by Kihei Onozuka was also taught by research people who returned from studying in Germany.

It is against this background that British diplomacy has matured. In the early 20th century, Britain produced Foreign Minister Gray to ease the world's competition for colonies, and in 1912 the London Conference was held to resolve the conflict in the Balkans through European cooperation. Furthermore, after World War I, the historian Morley was produced who advocated "new European cooperation", and "systems thinking" finally became the standard diplomatic idea of British diplomacy. In other words, in terms of "quality of diplomacy", it can be said that British diplomacy reached maturity in the first half of the 20th century. I think it should be emphasized that the background of Britain's stable diplomatic guidance, which reached maturity in the first half of the 20th century, is the intellectual tradition of continental rationalism and the "power of learning" connected to the "German School of History".

By the way, the "100 years of peace" in Europe under the Vienna system was broken by World War I (1914~1918). When the front expanded from all over Europe to the Middle East and Asia, and modern weapons such as tanks, airplanes, and poison gas were used in war for the first time and ended with the surrender of Germany, the aforementioned British historian Morley appealed for a "new European cooperation", and the politicians and diplomats under his influence once again envisioned the establishment of a permanent peace order like the Vienna system. From the point of view of the British, led by Morley, the League of Nations was also seen as a rehash of collective security during the Vienna regime. However, such attempts did not align with the intentions of each country, and eventually the international community entered World War II. If an international order based on a multilateral cooperative and stable multipolar structure had been born, as Morley thought, perhaps World War II could have been avoided.

Professor Kosaka's father, who was also a philosopher of the Kyoto School, who was influenced by me, highly appreciated British diplomacy aimed at international cooperation in the first half of the 20th century. After my son, Professor Masayao, who aspired to research British diplomacy, and his disciple, Professor Nakanishi, it led to my research emphasizing the "British School" and its origin, the "German School of History". By the way, I have never been directly taught, but I would like to add that from the perspective of collective security and international security, I was also influenced by Professor Yoshikazu Sakamoto of the University of Tokyo and Professor Takehiko Kamo of Waseda University.

By the way, the research of British international relations theory belonging to the "British School" that I value highly appreciated Helen's achievements mentioned above and aimed to "update Helen's scholarship". In this sense, the "British School" can also be positioned as a theorization of the "German Historical School", which historically examines international politics. Its main feature is the international order consisting of multilateral cooperation and a stable multipolar structure, and diplomatic thought based on "systems thinking" that integrates "ideals" and "reality" to realize it. Many of you may think that events such as the Napoleonic Wars and the Vienna System are written in world history textbooks a long time ago, but I hope you know that there are important perspectives and lessons included when thinking about lasting peace in the modern international situation.

In the first place, there are two premises behind the establishment of an extremely complete international order under the Vienna System. The first premise is the maturity of the soft side of the European international order in the late 17th and 18th centuries. At the same time that the Enlightenment was at its peak, the rationalist knowledge of philosophers and thinkers from German and French countries, including Pufendorff, Leibniz, Saint=Pierre, Rousseau, Wolff, and Vatttel, blossomed into "ideas related to collective security" and "ideas of international law", which were shared with politicians and diplomats in European countries. The European international order has matured on the soft side.

The second premise is that the process of maturation of the European international order has been clarified and visualized by a full-fledged research book. In 1809, just before Metternich began to lead international politics to European countries in earnest, a comprehensive research book on the maturation process of the European international order in the 15th~18th centuries was published, compiled by a German historian named Helen, which played a major role. Helen is a historian who is active as a Professor at the University of Göttingen and is regarded as the founder of the "German School of History" in international political history.

The European international order matured step by step from the 15th century to the early 19th century. First, (1) the "state of war" seen in the Italian War and the Thirty Years' War, (2) the "bipolar equilibrium" in which countries form a grand alliance against countries aiming for hegemony, such as Charles V's Habsburg Empire and Louis XIV's France, and (3) the "multipolar equilibrium" in which many great powers disperse and have power to form a harmonious balance when the grand alliance of various countries wins. We will proceed with the maturation of the hard side step by step. On top of this, the maturity of the soft side that I mentioned earlier was combined to form (4) "international cooperation (great powers)" operated by consensus among major powers, and (5) the "collective security system" in the early 19th century (1815~1822).

Against the backdrop of this maturation of the European international order as a "system," diplomatic thinking will undergo major changes. In the 18th century, in continental countries such as Germany and France, centered on Austria and Prussia, "systems thinking" became established to define diplomatic behavior based on the stability of the international order. To put it more precisely, "systems thinking" is a diplomatic thought that prioritizes the stability of the international community as a whole and pursues national interests within the scope of system stability, based on an understanding of the maturation process of the international system from the 15th century to the early 19th century. And the opposite of this was "opportunism". "Opportunism" is positioned as a diplomatic ideology that seeks every opportunity to promote national interests, and as a result, undermines the stability of the international system. In the countries of continental Europe in the 18th century, the mainstream of diplomatic thought changed from "opportunism" to "systems thinking", which strongly encouraged the maturity of the European international order. In other words, as countries emphasized diplomacy based on social considerations called "system thinking" rather than diplomacy based on selfishness called "opportunism", the international order changed (socialized) into an "international community" as a social union. Helen's achievement was research, which comprehensively summarized the maturity of the European international order as a "system" and "society." In other words, before the activities of Metternich and Karslerle, a specific methodology was established on how to create a stable and lasting peace order through the "power of learning".

By the way, in the period until the Vienna system in the first half of the 19th century, the center of "systems thinking" was on the continental side such as Germany and France, but "system thinking" was not mature in England until then. Originally, in Britain, there was no custom of thinking about diplomacy and international politics with the concept of "system", and in Britain during the Vienna System, "systems thinking" was understood only by a limited number of people who had close ties to Metternich, such as Carsleigh and Wellington. Rather, Britain's diplomatic guidance tended to focus on "opportunism" as represented by Canning and Palmerston, and to be eager to expand the British Empire. In the Seven Years' War in the mid-18th century, Frederick II of Prussia, who was betrayed by Britain's "opportunism" at the end of the war, criticized British diplomacy at the time in the sense that "Britain does not have the idea of systematically thinking about international politics", and "the dishonest white island (England)" was also synonymous with opportunistic British diplomacy. This point is described in the famous Harold Nicholson's book "Diplomacy".

However, when Helen's research was translated into English in 1834, British diplomacy gradually changed. The German word "Staatensystem", which had been used to refer to the "system of states (international system)" in Helen's English translation, was translated as "states system" for the first time in the English-speaking world, and as close academic exchanges with Germany developed, "system thinking" that thinks about international politics with the concept of "system" gradually became popular in the United Kingdom became established.

This is because in the 19th century, academic exchanges between research German and British scholars were active, and research who had mastered German full-fledged scholarship took up important positions at Oxford and Cambridge universities. Sir John Acton, who studied at the University of Munich for seven years and held the top Professor position of Professor (Regius Professor) in charge of the Course of modern history at the University of Cambridge, is a typical example. Especially after the reunification of Germany in 1871, German universities occupied the world's throne and were ranked among the world's research in all fields, and Germany was the first destination for research and social leaders in both the United States and the United Kingdom.

In this context, even in the international political research that was carried out within the framework of history, the research of the "German School of History" based on the aforementioned "history of international politics with Helen as the founder" and "diplomatic history with Ranke as the originator" will have an impact on the world. The Course of "Diplomatic History" established at Tokyo College (now Waseda University) and Tokyo Imperial University during the Meiji era is also the source of international politics and international relations theory in the current Japan, but it was established as the study of the "German School of History" spread around the world. Not only the "diplomatic history" represented by Nagao Ariga, but also the entire "political science" represented by Kihei Onozuka was also taught by research people who returned from studying in Germany.

It is against this background that British diplomacy has matured. In the early 20th century, Britain produced Foreign Minister Gray to ease the world's competition for colonies, and in 1912 the London Conference was held to resolve the conflict in the Balkans through European cooperation. Furthermore, after World War I, the historian Morley was produced who advocated "new European cooperation", and "systems thinking" finally became the standard diplomatic idea of British diplomacy. In other words, in terms of "quality of diplomacy", it can be said that British diplomacy reached maturity in the first half of the 20th century. I think it should be emphasized that the background of Britain's stable diplomatic guidance, which reached maturity in the first half of the 20th century, is the intellectual tradition of continental rationalism and the "power of learning" connected to the "German School of History".

By the way, the "100 years of peace" in Europe under the Vienna system was broken by World War I (1914~1918). When the front expanded from all over Europe to the Middle East and Asia, and modern weapons such as tanks, airplanes, and poison gas were used in war for the first time and ended with the surrender of Germany, the aforementioned British historian Morley appealed for a "new European cooperation", and the politicians and diplomats under his influence once again envisioned the establishment of a permanent peace order like the Vienna system. From the point of view of the British, led by Morley, the League of Nations was also seen as a rehash of collective security during the Vienna regime. However, such attempts did not align with the intentions of each country, and eventually the international community entered World War II. If an international order based on a multilateral cooperative and stable multipolar structure had been born, as Morley thought, perhaps World War II could have been avoided.

Professor Kosaka's father, who was also a philosopher of the Kyoto School, who was influenced by me, highly appreciated British diplomacy aimed at international cooperation in the first half of the 20th century. After my son, Professor Masayao, who aspired to research British diplomacy, and his disciple, Professor Nakanishi, it led to my research emphasizing the "British School" and its origin, the "German School of History". By the way, I have never been directly taught, but I would like to add that from the perspective of collective security and international security, I was also influenced by Professor Yoshikazu Sakamoto of the University of Tokyo and Professor Takehiko Kamo of Waseda University.

By the way, the research of British international relations theory belonging to the "British School" that I value highly appreciated Helen's achievements mentioned above and aimed to "update Helen's scholarship". In this sense, the "British School" can also be positioned as a theorization of the "German Historical School", which historically examines international politics. Its main feature is the international order consisting of multilateral cooperation and a stable multipolar structure, and diplomatic thought based on "systems thinking" that integrates "ideals" and "reality" to realize it. Many of you may think that events such as the Napoleonic Wars and the Vienna System are written in world history textbooks a long time ago, but I hope you know that there are important perspectives and lessons included when thinking about lasting peace in the modern international situation.

Why did Russia invade Ukraine?

In February 2022, the Russian military launched an invasion of Ukraine. This was a clear violation of the UN Charter and international law, and the responsibility for starting this war undoubtedly lies with the Putin regime in Russia. But why did Russia take such an outrageous action?

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, which had been a global superpower alongside the United States, a "power vacuum" emerged in the former Soviet regions of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. This power vacuum manifested itself in the form of the Bosnia-Herzegovina conflict in the former Yugoslavia region of Eastern Europe that began in April 1992, conflicts over the Caucasus region of the former Soviet Union, and the First Chechen Conflict at the end of 1994, between the Chechen Republic, which sought independence from Russia, and Russia, which tried to prevent this.

Amid these trends, many former Eastern European and Soviet countries began to aspire to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the collective defense system for Europe and North America. As these countries moved one after another toward full NATO membership, relations between Russia and the United States gradually deteriorated, and hopes for the establishment of a stable international security system in post-Cold War Europe gradually faded. It's true that at the time, some argued that membership in NATO, a "collective defense system" formed amidst the hostile East-West conflict, was a prerequisite for establishing a "collective security system," but this is also a bit of a strange argument.

Collective security, like the Quintuple Alliance (or Quintuple Alliance) under the Vienna System, is a system that transcends ideological conflict and aims to resolve problems through discussion within a universal framework that includes all major powers. Therefore, in the post-Cold War European framework, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which includes Russia as a member, should have been at the center, rather than NATO, which views Russia as a hypothetical enemy. However, as a result of the political process of the 1990s, NATO became the center of European security, pushing aside the OSCE. From Russia's perspective, this "NATO eastward expansion" poses a threat to its own security. Thus, the United States and EU countries failed to build a new international security system after the Cold War, and as a result, they pushed Russia, a major power, into a corner.

Pushing a particular country into a corner rarely produces good results. The conflict between the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance, one of the main causes of World War I, was originally the result of an alliance centered on Germany encircling France during the Bismarck regime (1871-1890) and pushing it too hard. The reaction to the encirclement of France unfolded after Bismarck's retirement, and the Triple Entente was formed by bringing Britain into the Franco-Russian Alliance (1894) formed by France, which had been released from the encirclement, and Russia, which had been accumulating dissatisfaction.

Japan, too, was driven into a corner and continued its reckless war. This was the result of pursuing opportunism and pursuing national interests and short-sighted survival strategies in an East Asian international order where the "system" was still immature. In June 1944, the Japanese Navy's Combined Fleet suffered a devastating defeat in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, followed by the fall of Saipan in July. On the European front, from June to August, Nazi Germany lost its main fighting force in a series of battles following Operation Bagration on the Eastern Front and the Normandy Landings on the Western Front. Paris was liberated, and Soviet forces advanced close to the German border on the Eastern Front. In other words, the outcome of World War II was decided between June and August 1944, and, according to common sense in European international political history, this was the time to begin peace negotiations aimed at establishing a stable postwar international order. Peace negotiations after a major war are conducted with the formation of the next international order in mind, so it is common for them to be led by the side that holds the initiative in the war, just as Metternich did in leading the formation of the international order at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. If the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union, which held complete control over the war, had not completely destroyed the defeated countries as they did at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, but had instead conducted peace negotiations with an eye toward regime change in the defeated countries and a stable multipolar order after the war in mind, it is possible that even greater casualties in Europe and East Asia could have been avoided. The massacres in Poland, the enormous losses at the fall of Berlin, the brutal battles on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the massive air raids on Tokyo and Osaka, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki might also have been avoided. Furthermore, if Japan and Germany had returned to parliamentary democracy and remained as major middle-class powers, the United States and the Soviet Union, with their extremely different ideologies, would not have come into direct contact with each other in Central and Eastern Europe and East Asia, and the Cold War, in which the East and West glared at each other over the "nuclear terror," might not have taken place. If only America and Churchill in Britain at the time had promoted the construction of a solid peaceful order based on "systems thinking," premised on discussions such as the "English School" and the "German Historical School," and abandoned policies that thoroughly cornered specific countries... I cannot help but regret this.

Of course, I have no intention of downplaying the enormous casualties that had occurred up until then in East Asia, particularly China and Southeast Asia, and in Europe, particularly Eastern Europe and Russia. However, the discussion of how these casualties could have been avoided is not related to the end of the war, but rather to the start and causes of the war, and so due to space constraints, I will not go into detail here.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, which had been a global superpower alongside the United States, a "power vacuum" emerged in the former Soviet regions of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. This power vacuum manifested itself in the form of the Bosnia-Herzegovina conflict in the former Yugoslavia region of Eastern Europe that began in April 1992, conflicts over the Caucasus region of the former Soviet Union, and the First Chechen Conflict at the end of 1994, between the Chechen Republic, which sought independence from Russia, and Russia, which tried to prevent this.

Amid these trends, many former Eastern European and Soviet countries began to aspire to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the collective defense system for Europe and North America. As these countries moved one after another toward full NATO membership, relations between Russia and the United States gradually deteriorated, and hopes for the establishment of a stable international security system in post-Cold War Europe gradually faded. It's true that at the time, some argued that membership in NATO, a "collective defense system" formed amidst the hostile East-West conflict, was a prerequisite for establishing a "collective security system," but this is also a bit of a strange argument.

Collective security, like the Quintuple Alliance (or Quintuple Alliance) under the Vienna System, is a system that transcends ideological conflict and aims to resolve problems through discussion within a universal framework that includes all major powers. Therefore, in the post-Cold War European framework, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which includes Russia as a member, should have been at the center, rather than NATO, which views Russia as a hypothetical enemy. However, as a result of the political process of the 1990s, NATO became the center of European security, pushing aside the OSCE. From Russia's perspective, this "NATO eastward expansion" poses a threat to its own security. Thus, the United States and EU countries failed to build a new international security system after the Cold War, and as a result, they pushed Russia, a major power, into a corner.

Pushing a particular country into a corner rarely produces good results. The conflict between the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance, one of the main causes of World War I, was originally the result of an alliance centered on Germany encircling France during the Bismarck regime (1871-1890) and pushing it too hard. The reaction to the encirclement of France unfolded after Bismarck's retirement, and the Triple Entente was formed by bringing Britain into the Franco-Russian Alliance (1894) formed by France, which had been released from the encirclement, and Russia, which had been accumulating dissatisfaction.

Japan, too, was driven into a corner and continued its reckless war. This was the result of pursuing opportunism and pursuing national interests and short-sighted survival strategies in an East Asian international order where the "system" was still immature. In June 1944, the Japanese Navy's Combined Fleet suffered a devastating defeat in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, followed by the fall of Saipan in July. On the European front, from June to August, Nazi Germany lost its main fighting force in a series of battles following Operation Bagration on the Eastern Front and the Normandy Landings on the Western Front. Paris was liberated, and Soviet forces advanced close to the German border on the Eastern Front. In other words, the outcome of World War II was decided between June and August 1944, and, according to common sense in European international political history, this was the time to begin peace negotiations aimed at establishing a stable postwar international order. Peace negotiations after a major war are conducted with the formation of the next international order in mind, so it is common for them to be led by the side that holds the initiative in the war, just as Metternich did in leading the formation of the international order at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. If the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union, which held complete control over the war, had not completely destroyed the defeated countries as they did at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, but had instead conducted peace negotiations with an eye toward regime change in the defeated countries and a stable multipolar order after the war in mind, it is possible that even greater casualties in Europe and East Asia could have been avoided. The massacres in Poland, the enormous losses at the fall of Berlin, the brutal battles on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the massive air raids on Tokyo and Osaka, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki might also have been avoided. Furthermore, if Japan and Germany had returned to parliamentary democracy and remained as major middle-class powers, the United States and the Soviet Union, with their extremely different ideologies, would not have come into direct contact with each other in Central and Eastern Europe and East Asia, and the Cold War, in which the East and West glared at each other over the "nuclear terror," might not have taken place. If only America and Churchill in Britain at the time had promoted the construction of a solid peaceful order based on "systems thinking," premised on discussions such as the "English School" and the "German Historical School," and abandoned policies that thoroughly cornered specific countries... I cannot help but regret this.

Of course, I have no intention of downplaying the enormous casualties that had occurred up until then in East Asia, particularly China and Southeast Asia, and in Europe, particularly Eastern Europe and Russia. However, the discussion of how these casualties could have been avoided is not related to the end of the war, but rather to the start and causes of the war, and so due to space constraints, I will not go into detail here.

The world needs a new collective security system

This year marks exactly 80 years since the end of World War II in 1945. Despite the dramatic changes in the international situation since then, the permanent Director, Board of Directors of the United Nations Security Board of Directors (SC) are still composed of the victorious nations of World War II. This means that Germany, now one of the central powers of the EU, and Japan, one of the original G7 members, are not permanent members of the Security Director, Board of Directors. This is because they were defeated in World War II. However, under the Vienna System, France, the defeated nation, returned to international politics in 1818, three years after the Congress of Vienna, as a major power with equal voice as the victorious nations. The Vienna System was originally designed with France's return as a major power in mind. Furthermore, India, a major power in the Global South, is not currently a permanent Director, Board of Directors. Given the current international situation, is it conceivable to build an international cooperation or collective security system that excludes Germany, Japan, and India?

I believe the world needs a new collective security system. A stable multipolar structure will facilitate international cooperation so that no country harbors significant dissatisfaction with the international system. A collective security system governed by stable consensus among nations will be built on this foundation. Such a structure must be steadily established. Furthermore, I believe that careful deliberation and reform are necessary to determine the universal common interests of the "world as a whole" that should be protected in the operation of the collective security system. The so-called "Western" justice centered around the G7, as has been the case until now, will not immediately become the justice of the "world as a whole." For "Western" justice to once again become the justice of the "world as a whole," the "Western" economic and social system must achieve a more equitable, fair, and mature state and gain persuasive power in the "world as a whole." Understanding and dialogue with the "non-Western world" is also crucial. Perhaps this is the mission of the next generation. Even if you do not become diplomats or politicians, I believe that in the future, you students will be faced with the turbulent international situation in your careers and careers more than our generation. In doing so, learning about the history of how humanity has sought to create a world free of conflict since the beginning of international politics at the end of the 15th century (1494) will enable students to consider different approaches and solutions from multiple angles and make life choices based on reason and intelligence.

To create a peaceful world, we need both idealism and realism. When I talk to students at Asia University, some initially say realist things like, "After all, power and money are what matter," but as I give more Lecture, they soon change their mind and say, "I think it's important to have ideals and virtues as a person, after all." Seeing students grow like this is the greatest reward for me as a teacher, and it gives me hope for the future.

Incidentally, in my seminar on "International Politics," we conduct research on international affairs and global governance, as I have mentioned above, but we also place great emphasis on teamwork and camaraderie among our seminar members. In particular, during our summer seminar camp at Lake Kawaguchi in Yamanashi Prefecture, we all work together to cook, have fun at badminton research, and have a blast. Students who have honed their perspectives on international politics and their communication skills in the seminar are doing well in their job searches at major companies and in the civil service, and I sincerely hope that they will make significant contributions to the realization of a prosperous and peaceful Japan and world in the future.

I believe the world needs a new collective security system. A stable multipolar structure will facilitate international cooperation so that no country harbors significant dissatisfaction with the international system. A collective security system governed by stable consensus among nations will be built on this foundation. Such a structure must be steadily established. Furthermore, I believe that careful deliberation and reform are necessary to determine the universal common interests of the "world as a whole" that should be protected in the operation of the collective security system. The so-called "Western" justice centered around the G7, as has been the case until now, will not immediately become the justice of the "world as a whole." For "Western" justice to once again become the justice of the "world as a whole," the "Western" economic and social system must achieve a more equitable, fair, and mature state and gain persuasive power in the "world as a whole." Understanding and dialogue with the "non-Western world" is also crucial. Perhaps this is the mission of the next generation. Even if you do not become diplomats or politicians, I believe that in the future, you students will be faced with the turbulent international situation in your careers and careers more than our generation. In doing so, learning about the history of how humanity has sought to create a world free of conflict since the beginning of international politics at the end of the 15th century (1494) will enable students to consider different approaches and solutions from multiple angles and make life choices based on reason and intelligence.

To create a peaceful world, we need both idealism and realism. When I talk to students at Asia University, some initially say realist things like, "After all, power and money are what matter," but as I give more Lecture, they soon change their mind and say, "I think it's important to have ideals and virtues as a person, after all." Seeing students grow like this is the greatest reward for me as a teacher, and it gives me hope for the future.

Incidentally, in my seminar on "International Politics," we conduct research on international affairs and global governance, as I have mentioned above, but we also place great emphasis on teamwork and camaraderie among our seminar members. In particular, during our summer seminar camp at Lake Kawaguchi in Yamanashi Prefecture, we all work together to cook, have fun at badminton research, and have a blast. Students who have honed their perspectives on international politics and their communication skills in the seminar are doing well in their job searches at major companies and in the civil service, and I sincerely hope that they will make significant contributions to the realization of a prosperous and peaceful Japan and world in the future.

Related Links

- Faculty of Law TOP

- Faculty Faculty of Law Faculty Introduction

- Introduction to Faculty of Law Department of Law

- Faculty of Law Department of Law Four Years of Learning

- Faculty of Law Department of Law Registration Model

- Faculty of Law Department of Law Class Introduction

- Faculty of Law Department of Law Seminar

- Faculty Faculty of Law Department of Law Employment Measures

- Faculty introduction of Faculty of Law Department of Law